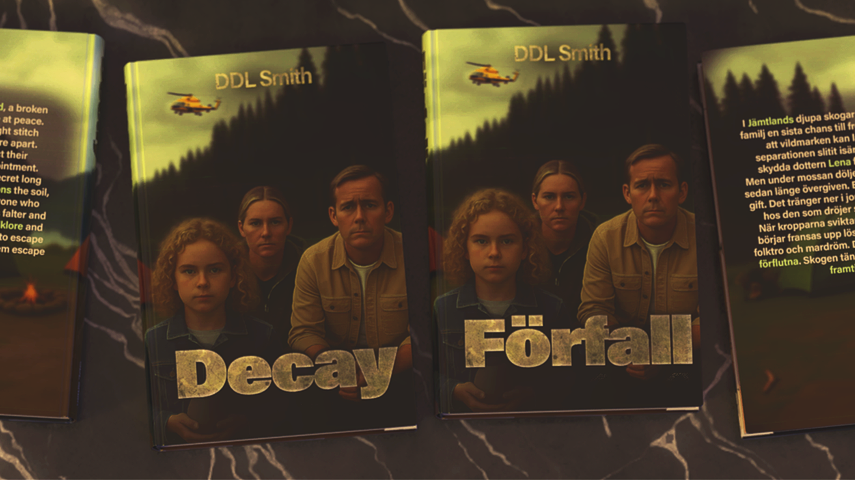

Decay and Me

Some fears take shape in statistics; others in silence. When I began researching what would become Decay, I didn’t set out to write about radiation, folklore, or even the weight of the earth itself. I set out to write about unease. The kind that lingers when landscapes seem altered, when stories carry warnings you cannot quite dismiss, when headlines turn risk into panic.

Over the past months, I have shared fragments of that journey: how land remembers its scars, how folklore gives voice to forests, how nuclear power is as much about perception as physics. Each article has been an attempt to trace the shape of fear. Yet what surprised me most was how naturally those threads converged, not only in research but in story. Decay became the meeting point where fact, myth, and imagination pressed against one another.

I began with the idea of radiation from an orphan source. At first I imagined it as the seed of a thriller, a straightforward tale of danger and pursuit. But as I wrote, the story changed and grew. Writing it as horror meant allowing the unease to creep slowly, to sit in silence rather than spectacle. Folklore entered later, not as decoration but as discovery, shaping the novel in ways I had not planned at the beginning. Let’s go though the elements of Decay.

The Earth Remembers

Some places feel heavy before you even know their history. That sensation. The silence of a clearing, the unease of a space that refuses to be ordinary was the first spark that made me realise Decay would not be built on spectacle, but on persistence.

Radiation became the perfect metaphor for this. It lingers unseen, altering lives without ever announcing itself. That invisibility haunted me. In the novel, the orphan source is more than a plot device; it is a way to give form to the idea that land carries memory longer than people do. Horror here does not arrive with fire or noise. It creeps quietly, unsettling not through what is visible but through what refuses to be seen.

As I wrote, I returned again and again to the thought that trauma, like radiation, is inherited. Families fracture under burdens they cannot see, carrying echoes of events never spoken aloud. The characters in Decay grew from that realisation: that what we bury in soil or memory never truly disappears.

Folklore in Decay

When I travelled to Östersund, I thought I was chasing setting: lakes, forests, weather patterns. What I found instead was a voice. Not a literal one, but the presence that folklore has always given to the land. In Decay, that voice emerged through the Vittra beneath the soil, the Skogsrå among the trees, and the sorrowful Myling that never rests.

They were never part of the plan. Yet as I wrote, they settled into the story as though they had always been waiting. The Vittra reminded me that what lies hidden still demands respect. The Skogsrå carried the ambiguity I wanted in the forest: beauty and danger blurred together. And the Myling offered the most human terror of all: grief that refuses to stay buried.

Folklore gave shape to what science could not. Radiation has no face, no voice, but in these figures the land could judge, remember, and mourn. Their presence turned silence into something charged. Fear in Decay comes not only from what is real, but from what we sense might be.

Nuclear Fear and Public Perception

Fear around radiation has never been shaped by numbers alone. It has been shaped by the images that linger in memory: a firefighter’s blistered skin, an abandoned city, the symbol of trefoil on a locked gate. That weight of imagination became as important to Decay as the science itself.

When I began drafting, I realised that the family at the centre of the story did not need to witness catastrophe to feel its presence. Their unease comes from suggestion, from the suspicion that something invisible might be at work. They argue, they falter, and their own thoughts fill the silence. In that way, perception drives the novel more than exposure ever could.

What unsettles in Decay is not spectacle, but the stories that build around it. Horror does not come only from the danger itself, but from what we believe the danger might be. That belief, fragile and persistent, is what carries the novel forward.

It is important to make a distinction here. The fear in Decay belongs to fiction. The novel imagines radiation as a metaphor for memory, unease, and the scars left behind. It uses the word “nuclear” in the language of story, not in the language of policy or engineering.

Real-world nuclear power is something different: regulated, scrutinised, and built on decades of safety measures. The reactors at Hinkley Point or Sizewell C are not the forests of Decay. The novel is not a commentary on the industry itself, but an exploration of how fear and imagination work.

Bringing It Together

Looking back across the novel, I see the same thread running through every element: memory. The earth remembers its scars. Folklore remembers what language cannot explain. And we, as people, remember the images that frighten us long after the numbers have faded. Decay became my attempt to bind those memories into a single story, one that unsettles not through spectacle but through persistence.

Writing fear is not about inventing monsters. It is about recognising the ones already present in our landscapes, our histories, our families. Fear endures because it is remembered, and Decay is a novel about what happens when memory refuses to fade.

In seven days, that story will no longer be mine alone. Decay releases on 10 October, and soon readers will be able to step into those forests, hear their silence, feel their weight, and decide what it is the land remembers.